The coincident issue of two quality-risk-management-driven draft guidance documents by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in August 2011 has been considered by many stakeholders and observers as a paradigm shift in clinical quality risk management (CQRM). Both documents, FDA’s guidance entitled 'Oversight of Clinical Investigations - A Risk-Based Approach to Monitoring,‘ which was finalized in August 2013 [1], and EMA’s draft ‘Reflection Paper on Risk-Based Quality Management in Clinical Trials’ [2], have triggered a myriad of blogs, discussions, webinars and conference presentations focusing on the modernization of clinical trial operations and conduct.

The perception of the two guidance documents have often been confined to the issues of ‘risk-based monitoring’ and ‘centralized monitoring,' as the current practice of source-data verification, and intense on-site monitoring has a very strong economic impact on the overall drug development costs. However, both the US and EU regulatory authorities set up that guidance not solely with an intent to contribute to a leaner and more efficient clinical operations approach and foster ‘better-quality’ clinical trials, but also to inspire stakeholders’ conception of innovative drug development methods and edify a 21st century-like regulatory process infrastructure.

This article discusses the impact of the risk-based approach in clinical drug research on regulatory decision-making, outlines the new role of CQRM for the benefit-risk evaluation process, and sketches the relevance of the new quality paradigm for the overall drug lifecycle management process.

Hauling Modernization: The Long-lasting Impact of the U.S. Critical Path Initiative

The initial starting point for the current initiatives to modernize the conduct of clinical drug trials is FDA’s ‘Critical Path Initiative,’ launched in March 2004 with the release of FDA’s landmark report ‘Innovation/ Stagnation: Challenge and Opportunity on the Critical Path to New Medicinal Products’ [3]. The initiative lays out FDA’s strategy to drive innovation in the scientific processes through which medical products are developed, evaluated and manufactured. Through a ‘Critical Path Opportunities List’ and several subsequent reports on key achievements,

FDA identified a number of “21st century challenges” for the overall drug development process, and implemented the basis for the socalled “critical path research”, directed towards improving the product development process itself by establishing new evaluation tools. From the beginning, “streamlining clinical trials” has been a key topic within this high-level initiative, which also enforces biomarker research and the “moving (of) manufacturing into the 21st century” [4], also encompassed by the ‘cGMP’ approach [5].

Since, numerous achievements have been made in the R&D process modernization, including the finalization of the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) quality guidelines ICH Q8 - Q10 [6- 8]. This introduced the quality risk management principles and concepts generated under the auspices of the International Standardization Organization (ISO) to the pharmaceutical development process, and the ‘Clinical Trials Information Initiative’ (CTTI), a public-private partnership aimed to identify and promote practices that will increase the quality and efficiency of clinical trials [9,10]. Regarding the modernization of the clinical trial conduct process, initiatives in other regions focused on the implementation of risk-based approaches to the management of clinical trials, too [11,12].

The Perception of ‘Risk’ in Clinical Trials is Subject to Change

In all of these recent endeavors, the notion and definition of what ‘risk’ may constitute in the context of a clinical trial played a central role. This issue had been neglected in the ICH-GCP standard [11] which had seen no major revision since coming into force in May 1996 – at a time when the aforementioned conceptual basis for quality risk management in the pharmaceutical sector simply did not exist! Similarly, the common EU framework for clinical trials, legally enshrined by the enforcement of the EU Clinical Trials Directive 2001/20/EC in May 2004, also did not pay attention to the risk issue. The only notion is made in the introductory recitals: “the clinical trial subject’s protection is safeguarded through risk assessment".

The clinical trial legislation in the EU will change in 2014. The new legislation – a legislative proposal issued by the EU Commission [13] is currently under discussion at the European Parliament – will definitively change in this matter: the risk to patient safety and the risk to data reliability and robustness will constitute the two principal and equal risk determinants. By this move, the EU lawmaker catches up with the tremendous evolution of quality risk standards and follows calls to introduce the risk-based governance approach in the clinical trials sector, too [14]. Risk-based trial authorization and supervision processes constitute a relevant portion of the legislative overhaul.

The previously mentioned EMA reflection paper on quality risk management in clinical trials [2] anticipates and mirrors this paradigm shift: risks related to a clinical trial are no longer confined to the notion of “risks and inconveniences for the subject”, i.e. the patient(s) participating in a clinical trial, but are now extended to the notion of “risks to the anticipated therapeutic and public health benefit(s)”, which might arise from poor data quality, unreliable trial conduct, or inadequate trial robustness. In this context, both authorities – the FDA as well as the EMA – put much emphasis on a systematic, proportionate approach to the overall clinical development process, applying process controls continuously. In addition, both authorities agree that the trial protocol itself is the “blueprint for quality”, by which a sponsor shall prospectively identify important risks to subject safety and data reliability. Therein, trial monitoring is just one component of a multi-factor approach to ensure the quality and integrity of clinical research.

Input on Regulatory Authorities’ Overall Decision Making

Given the current landscape, trial sponsors recognize that better risk identification and risk assessment processes are key. The ISO tools exist and have been adapted through the ICH Q8 - Q10 guideline set to the pharmaceutical development process although many stakeholders consider its scope limited mainly to the chemistry, manufacturing and control operations.

From the authorities’ viewpoint, the three guidelines are of overarching character and are applicable for “submission/review processes throughout the lifecycle of drug substances and drug (medicinal) products, biological and biotechnological products” [7]. Drug review and approval constitute the central authoritative actions by which authorities like the FDA or EMA exercise their powers and it is therefore not surprising that a direct interaction between the new quality paradigm and the processes of approving or suspending the commercialization of medical products is manifest.

In its recent reflection paper, the EMA defines quality as “fitness for purpose” and concludes that, in terms of the purpose of a clinical trial, quality shall serve “the right decision-making at the end". For the regulator this means that the right decision is taken regarding a specific drug’s approvability, but also – and this is the second dimension of quality data arising from clinical trials – regarding a medical doctor’s or health care payer’s decision to prescribe or reimburse a given drug.

A number of years ago, regulators in the US, like in the EU or other regions, began to engage in processes of continuous benefit-risk assessment and work out a contemporary benefit-risk methodology. The FDA, EMA, US industry (assisted by its trade association, PhRMA), and a consortium of several other medicines regulatory authorities, all contributed to the generation of more transparent and reproducible benefit-risk assessment methodologies [15-18]. All stakeholders aimed to promote regulatory science by the establishment of qualitative or even semi-quantitative assessment models, by which available evidence for a (new) drug’s safety and efficacy can be measured, compared and better-communicated. In this context, safety refers to any safety aspect arising from the pharmaceutical manufacturing quality, as well as from the pre-clinical and clinical development, and efficacy is related to all pre-approval evidence obtained by translational and clinical research.

Regarding the transposition of efficacy and safety findings into their benefit-risk assessment, the FDA and EMA benefit-risk frameworks are conceptually similar in terms of the elements being considered for inclusion [17]. However, FDA’s recently issued benefit-risk assessment draft implementation plan [15] shows a certain divergence to EMA’s approach by expressing “concerns on quantitative approaches", leading the US authority to opt for a ‘structured qualitative approach’ rather than a semi-quantitative approach, as its EU counterpart does. However, both agencies pay tremendous attention to the way uncertainties should be handled in key areas of their regulatory judgment – an issue of utmost importance in the evaluation of outcomes of primary endpoints in pivotal clinical trials.

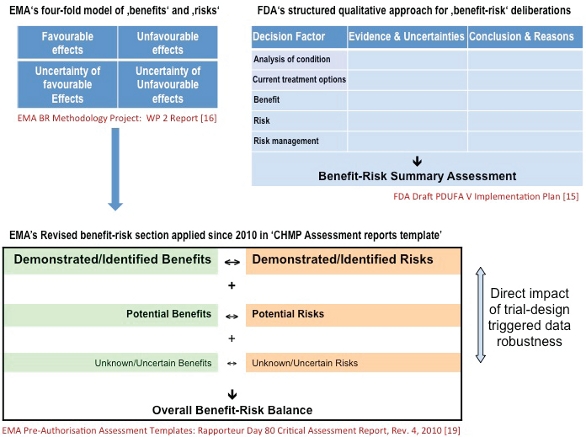

Figure 1 summarizes both authorities’ current benefit-risk-assessment approach. The EMA is a few steps ahead; since 2010 the agency has applied a ‘four-fold qualitative model’ for its regulatory decision-making [16], whereas the FDA still “plans to use a staged approach in implementing the benefit-risk framework in human drug review", forecasted to start in fiscal years 2014 and 2015 [15]. Most importantly, Figure 1 notes that the EU regulator now uses a staggered approach inside the agency’s reviewers’ assessment report template [19], in which the uncertainty of a benefit or risk variable directly determines the weight of the observed favorable or unfavorable effect. Additional EMA guidance published in January 2013 outlines how findings from GCP inspections will adequately be rated in terms of their relevance for the overall benefit-risk evaluation [20].

Figure 1. US and EU authorities’ new framework for benefit-risk based drug approval decisions

Figure 1. US and EU authorities’ new framework for benefit-risk based drug approval decisionsTherefore the CQRM function in companies is tremendously gaining relevance: its capacity to control and reduce the uncertainty variable plays a key role for future regulatory success.

Can Pharma Afford to Maintain its Singular Quality Management Model?

Nowadays, the pharmaceutical sector is witnessing the advent of this emerging quality paradigm for the overall drug development and lifecycle management process. After manufacturing and control, the new quality paradigm advocated by the ICH Q8 - Q10 guidance triad has also reached the core development functions. It is important to mention that the perception of risk in this new approach is different from the old conception of risk in clinical research: the notion of risk is neutral and emphasis is not placed on its avoidance, but on the systematic viewing of how to handle risks [14].

Pharma cannot maintain its old-fashioned, singular-industry quality management model. Drug development is enormously complex as it focuses on science and biology of the human, which is, in many aspects, far from being fully understood. However, pharma must change the ways in which quality is achieved and guaranteed during the entire R&D process. Quality is not a burden but a chance. Learning from other industries and from the ISO is not a threat but a possibility to better succeed in the face of frighteningly high attrition rates in drug development [21,22]. ISO’s toolbox for quality risk management is freely available; the tools have been validated thoroughly. Sharing and improving on best practices is a duty for all functions involved in the lifecycle management of a drug. These functions should adapt in the near future to the new quality paradigm. Growing commercial pressure and financial burden will drive the pharma industry’s move towards a holistic approach to quality risk management. “We do not have the time to do things right but have (still) the money to do things twice” – this witticism phrased during the Drug Information Association’s recently-held Annual Clinical Forum in Dublin [23] perfectly summarizes the current situation and the urgent need for change.

Moving towards an overall quality risk management model is not a cost-driver if the propagated ‘quality-by-design space’ is meaningfully used. To this respect, FDA’s desired state [9] for 21st century clinical development is directly deduced from the quality-by-design ideal introduced by ICH Q8 - Q10; authorities are keen to see maximally efficient, agile clinical development programs that reliably produce high quality data and protect trial participants without extensive regulatory oversight.

References

- FDA Guidance for Industry. Oversight of Clinical Investigations - A Risk- Based Approach to Monitoring. Procedural, August 2013 (OMB Control No. 0910-0733). http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/.../Guidances/UCM269919.pdf

- EMA. Draft reflection paper on risk based quality management in clinical trials. Compliance and Inspections, 4 August 2011. (EMA/INS/ GCP/394194/2011) http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_ library/Scientific_guideline/2011/08/WC500110059.pdf

- FDA. Report on Innovation/Stagnation: Challenge and Opportunity on the Critical Path to New Medical Products (March 2004). http:// www.fda.gov/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/CriticalPathInitiative/ CriticalPathOpportunitiesReports/ucm077262.htm

- FDA. Critical Path Opportunities List (March 2006). http://www.fda.gov/downloads/scienceresearch/specialtopics/criticalpathinitiative/criticalpathopportunitiesreports/UCM077258.pdf

- FDA. Pharmaceutical cGMPs for the 21st Century - A Risk-Based Approach (September 2004). http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/Manufacturing/ndAnswersonCurrentGoodManufacturingPracticescGMPforDrugs/UCM176374.pdf

- ICH. Guideline on Pharmaceutical Development (Q8) (November 2005, revised in November 2008 and August 2009). http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Quality/Q8_R1/Step4/Q8_R2_Guideline.pdf

- ICH. Guideline on Quality Risk Management (Q9) (November 2005). http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Quality/Q9/Step4/Q9_Guideline.pdf

- ICH. Guideline on Pharmaceutical Quality Systems (Q10). (June 2008) http://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/ Guidelines/Quality/Q10/Step4/Q10_Guideline.pdf

- Duke University. Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative. https://www.dtmi.duke.edu/public-private-partnerships/clinical-trials-transformationinitiative- ctti and http://www.trialstransformation.org/

- FDA. Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative (June 2009). http:// www.fda.gov/scienceresearch/specialtopics/criticalpathinitiative/ spotlightoncpiprojects/ucm083241.htm

- UK MRC/DH/MHRA joint project. Risk-adapted Approaches to the Management of Clinical Trials of Investigational Medicinal Products (October 2011). http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Howweregulate/Medicines/ Licensingofmedicines/Clinicaltrials/Submittinganotificationforatrial/ index.htm

- OECD. Recommendation on the Governance of Clinical Trials (March 2013). http://www.oecd.org/sti/sci-tech/oecd-recommendationgovernance-of-clinical-trials.pdf

- EU Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on clinical trials on medicinal products for human use, and repealing Directive 2001/20/EC (COM(2012) 369 final, 17 July 2012). http://ec.europa.eu/health/files/clinicaltrials/2012_07/ proposal/2012_07_proposal_en.pdf

- Hartmann M, Hartmann-Vareilles F. Concepts for the Risk-Based Regulation of Clinical Research on Medicines and Medical Devices. Drug Inf J 2012; 46(5):545-54. http://dij.sagepub.com/content/46/5/545

- FDA. Draft PDUFA V Implementation Plan: Structured Approach to Benefit-Risk Assessment in Drug Regulatory Decision-Making (February 2013) http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ForIndustry/UserFees/ PrescriptionDrugUserFee/UCM329758.pdf

- European Medicines Agency benefit-risk methodology project. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/ special_topics/document_listing/document_listing_000314. jsp&mid=WC0b01ac0580223ed6

- Walker S, McAuslane N, Liberti L. Developing a common benefitrisk assessment methodology for medicines – a progress report. Scrip Regulatory Affairs 2011; 23(12):18-21. http://cirsci.org/system/ files/private/SRA_Dec%202011_Developing_Walker_McAuslane_ Liberti%5B1%5D.pdf

- Coplan PM, Noel RA, Levitan BS, Ferguson J, Mussen F. Development of a Framework for Enhancing the Transparency, Reproducibility and Communication of the Benefit–Risk Balance of Medicines. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011; 89(2):312-5. http://www.nature.com/clpt/journal/v89/n2/full/ clpt2010291a.html

- EMA. Pre-authorisation assessment templates and guidance (September 2010).http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/regulation/ general/general_content_000121.jsp&mid

- EMA. Points to consider on GCP inspection findings and the benefit-risk balance, 19 September 2012 (EMA/868942/2011). http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2013/01/WC500137945. pdf

- Kola I, Landis J. Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nature Rev Drug Discov 2004; 3(8):711–716. http://www.nature.com/nrd/ journal/v3/n8/abs/nrd1470.html

- Widler B. Good Clinical Practice Global Trends 2012. The Monitor 2012; 26(5):9-13. http://www.nxtbook.com/nxtbooks/acrp/monitor_201209/index.php

- DIA. 7th Annual Clinical Forum Dublin 2013 – Final program (October 2013). http://www.diahome.org/Tools/Content.aspx?type=eopdf&file=% 2Fproductfiles%2F31375%2F13103_pgm.pdf

Markus Hartmann, Founder and Principal Consultant of European Consulting & Contracting in Oncology, has more than 15 years of experience in the clinical, medical and regulatory affairs business, with dedicated experience in clinical cancer research and multimodal therapeutic strategy trials and prior employment at ICON, Aventis Pharma and Merck. His specific interest is devoted to regulatory and legal questions surrounding clinical research on drugs, devices and diagnostics. He holds a Ph.D. in bioinorganic chemistry from the University of Heidelberg (1996) and a MA in Drug Regulatory Affairs from the University of Bonn (2006). Email: [email protected]