Abstract

This article explains the regulatory challenges FDA encounters with current manufacturers’ global outsourcing and the role and responsibilities for those participating in outsourcing. Through different kinds of cooperative arrangements, biotech drug manufacturing firms outsource parts of their manufacturing processes and services. Among the motivators to practice outsourcing, economics and faster product manufacturing play major roles. This new trend of doing business imposes new demands on FDA’s already limited resources. FDA wants to support every effort that would facilitate the approval of safe and quality products for the American public in the United States. Therefore, it is important to gain a full understanding on the impact outsourcing has on the firms and on the FDA, along with the responsibilities for the participants of these cooperative arrangements. This understanding can facilitate compliance with FDA regulations.

Introduction

This article explains the impact outsourcing has in defining the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) activities and its resources. Different cooperative manufacturing arrangements are possible for biotech product firms through outsourcing. Understanding these arrangements and the roles responsible for these cooperative manufacturing arrangements can help improve outsourcing practices and minimize the potential for quality problems.

Background

Originally, there were very few biotech product manufacturers in the U.S. These few manufacturers were responsible for the whole manufacturing process of their products. As time progressed, the increasing complexity of manufacturing and improved, highly specialized technologies began to limit single source manufacturing. Firms who previously had performed the entire process were now only capable of performing limited aspects of the whole drug manufacturing process. Consequently, firms started to delegate certain aspects of the manufacturing process to contract services to facilitate product development. Increased market pressure for innovation fostered even further specialization by outsourcing firms.

Furthermore, the new outsourcing trend is supported by current industry reports estimating that the number of offshore outsourcing contracts grew between 30% to 40% annually between 2003 and 2008, and annual spending in the global business services outsourcing market grew to over $150 billion by the end of 2006 [1]. Also, data from an exploratory survey of 86 companies suggests that the outsourcing of strategic activities such as manufacturing and clinical trials continue to be outsourced at an accelerating pace [2].

Cooperative Manufacturing Arrangements

A Type of Outsourcing

Outsourcing involves delegation of responsibilities among different manufacturers. The FDA Guidance to Industry – “Quality Systems Approach to Pharmaceutical CGMP Regulations [3],” defines outsourcing as, “the hiring of a second party to perform parts of the overall manufacturing process.” These specific legal arrangements pursue a goal: lower manufacturing costs and use of advanced technology to meet a specific manufacturing milestone. Accomplishing this goal via this type of outsourcing brings products to the market faster, often with less expense than if the parent company were required to develop, qualify and then implement all the manufacturing processes. Benefits from outsourcing include access to a skilled workforce without having to hire new workers [4] , higher-quality services provided by a focused and experienced external source, and being able to refocus limited internal resources on core business activities [5].

Description of the most common arrangements among firms sharing the manufacturing of a given product can be found in the FDA Guidance to Industry: “Cooperative Manufacturing Arrangements for Licensed Biologics [6].” The most frequent type of cooperative manufacturing arrangements described in this guidance includes manufacture of biological product by one firm and manufacture of the biological substance by another firm. At this time FDA Guidance to Industry: "Cooperative Manufacturing Arrangements for Licensed Biologics," is the only guidance addressing cooperative manufacturing arrangements so it is applicable interchangeable to drugs or biologics including biotech products." There are many other cooperative arrangements recognized by the FDA. For example, manufacture of the whole product might be done by one firm, with packaging or warehouse contracting performed by another. Another cooperative arrangement includes when a manufacturer might contract to have only laboratory testing performed by an outside source. A third possible cooperative arrangement is the exception of obtaining a small amount of product from a firm which is not part of the identified license holder. Also, there may be situations where manufacturing responsibilities are shared among two or more firms responsible for specific aspects of a product’s manufacture, or, situations where a firm performs all of the product manufacture as a service to the license holder.

In summary, any type of firm participating in the manufacturing process must comply with the Law.

Roles and Responsibilities Under the Law

Many are the benefits of outsourcing to those companies looking for innovation and building efficiency. More agile contract manufacturers and labelers are a great alternative. However, properly managing outsourced manufacturing presents many challenges to everyone [7]. With new challenges, responsibilities also need to be defined.

FDA defines each participant’s responsibilities within cooperative manufacturing arrangements based on the Code of Federal Regulation (21 CFR 600.3(t) and 21 CFR 610.13). Manufacturer is defined as, “the responsible entity to legally manufacture a drug.” This definition applies to license holders and contractors. However, the responsibilities of license holders differ from those of contractors.

Through the consistent implementation of current good manufacturing practices (cGMPs) the license holder can ensure compliance with product and establishment standards. The cGMPs ensure compliance with FDA regulations. As required by the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), the license holder also reports changes in production and facilities according to the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) and identifies all contractor manufacturers responsible for the manufacture of the product (see PHS Act, 21 CFR Parts 210, 211, 600 through 680, and 820).

FDA recommends effective and timely communication with the parties involved in the manufacturing of a product to avoid misunderstandings. Communication is extremely important in supporting the production of high-quality biopharmaceuticals. This is especially true when the results of an analysis indicate a problem with the product [8]. Examples of communications considered effective by the firms include timely notification of AE’s to FDA and deviations in manufacturing to the license holder. Reporting any test results that may adversely affect the product, informing manufacturing changes to all the parties involved in the manufacture, and informing every manufacturing participant on changes in facilities are all good examples of effective communication.

There are different mechanisms available to facilitate effective communication between firms and contractors. For example, there are two options contractors may use to notify license holders about a recent change. One option is to provide the information to the sponsor to submit as a supplement to the original biologic licensing application (BLA) to FDA. The second is to provide the license holder with an authorization letter to review the contractor’s Drug Master File (DMF), while sending an additional letter to the FDA authorizing FDA to review the DMF on behalf of the BLA [9] (See 21 CFR Part 20, 21 CFR 314.420, and 21 CFR 314.430 for more details). In practice, the latter option is the most commonly used due to confidentiality issues surrounding proprietary manufacturing changes. FDA reminds all firms and contractors that DMFs are not FDA-approved documents. However, issues or problems with DMFs may prevent FDA from approving a submission.

Outsourcing does not exempt its participants to comply with the Law, regulations, and cGMPs. Not complying with these can result in adverse action taken by FDA against the firms. For more details on how license holder and contractors can comply with FDA regulations, please refer to the FD & C Act or the CFRs.

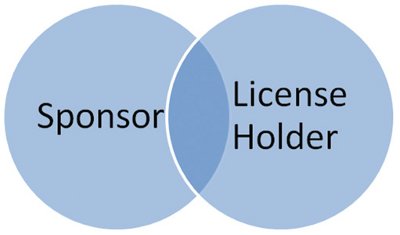

Figure 1

Sponsor Versus License Holder

According to FDA’s guidance, a sponsor is an individual or pharmaceutical company, governmental agency, academic institution, private organization, or other organization who takes responsibility for and initiates a clinical investigation [9]. A license holder is an applicant for a license assuming responsibility for ensuring compliance with applicable product and establishment standards. The applicant is not required to perform any of the manufacturing steps but may contract other firms to perform all or part of the manufacture of the product [10]. A sponsor can be a license holder and a license holder can be a sponsor. Sponsorship and license holding are not mutually exclusive or totally inclusive.

Effects of Outsourcing on FDA Resources

We benefit from one of the safest drug supplies and one of the highest standards of consumer protection in the world. However, the general trend toward global outsourcing of pharmaceutical products has created new challenges for the FDA. New consumer safety risks and challenges result when outsourcing the manufacturing of pharmaceutical products [11].

Complexity in the outsourcing arrangement likewise, means complexity for FDA’s oversight. For example, a biological component material made in one facility may have important precursor constituents made elsewhere, and an important property of the material may be adjusted by yet another facility. The product might then be sent to an additional separate facility to be filled into containers. In this scenario multiple contractors could be involved in the manufacture of a single compound!

Nowadays, modality is to have a manufacturing process shared among different participating sites. When the manufacturing activities are outsourced, control of the product’s quality has to be maintained [12]. There is a positive relationship between the number of firms participating in the manufacture of a product and the number of FDA inspections. Inspections to sites, including laboratories, suppliers, labelers, storage sites, and packagers – in and outside the United States will be needed. Warehouses for unlabeled products may also be inspected. The increase in FDA inspections has posed new challenges to FDA, including meeting this obligation with limited resources. The need to perform inspections overseas has increased as firms have moved manufacturing outside the U.S., often to reduce costs. In today’s global manufacturing environment, a BLA approval may require more than three inspections in different states or foreign nations. In the past, less inspectional obligations, and normally of US sites, may have been needed before approval.

Increase in worldwide inspections is associated with an increase in travel time and associated expenses such as the need for multilingual staff to manage and control documentation, and interaction with a variety of international business cultures. In their interactions with manufacturing sites outside the U.S. different countries translate into differences on regulatory requirements and compliance modalities.

These challenges translate into an increased need for effective communication and coordination of efforts with more parties.

In response to these new challenges, new trends have emerged: (1) utilization of technology and electronic meetings via new communication modalities to facilitate communication between the FDA and other countries’ national drug regulatory programs; (2) increased FDA information needs before a product’s approval; and (3) the need for more and broader-reaching evaluations in support of inspection planning.

Recommendations to Drug Manufacturers

Following FDA’s guidance will ensure thorough and comprehensive submissions. To save time, FDA encourages early communication between the sponsor and the Agency. Including a table of contents with each submission, a list of acronyms with their definitions, background information, past history and future projections are all good time-saving practices. Another current issue that may impact the future of outsourcing is the development of Generics for DNA-derived biotech and therapeutics covered under BLAs. This issue is currently being studied by Congress and FDA.

Conclusion

In conclusion, FDA wants to facilitate product development and manufacturing flexibility. It supports advancement of new and innovative ways that will lower the cost of drug development while advancing the critical path for drug products’ review. Manufacturers should have a clear understanding of the potential role of cooperative manufacturing arrangements for outsourcing in their manufacture process and their responsibilities in the context of such cooperative manufacturing arrangements. A well-written agreement can help avoid regulatory actions with legal consequences [13].

Footnote: This article was written by the author in her private capacity. No official support or endorsement by the Food and Drug Administration is intended or should be inferred.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for all the editorial changes, guidance, and clearance received from the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, FDA, Office of New Drugs, Division of Gastroenterology Products and the Division of Manufacturing Product Quality for making this publication possible.

Abbreviations

FDA – Food and Drug Administration

CDER- Center for Drug Evaluation and Research

cGMP – current Good Manufacturing Practices

CFR – Code of Federal Regulations

DMF – Drug Master File

BLA – Biologic License Application

DNA – deoxyribonucleic acid

SOPs – Standard Operational Procedures

USC – United States Code

References

- Kroes, J. “Firm Value Impacts of Offshore Business Services Outsourcing” (2009) 2009 Northeast Decision Sciences Institute Proceedings, pag. 302–307.

- Sen, A. & MacPherson, A. “Outsourcing, External Collaboration, and Innovation among U.S. Firms in the Biopharmaceutical Industry” (2009) The Industrial Geographer, 6(1) pag. 20–36.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry. Quality Systems approach to pharmaceutical CGMP regulations. Rockville, MD; 2006 Sept. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM070337.pdf.

- Kripalini, M., Engardio, P. & Hamm, S. “The Rise of India: Growth is only just starting, but the country’s brainpower is already reshaping Corporate America” (2003) Business Week, retrieved August 11, 2009 from Business Source Complete database.

- Embleton, P. & Wright, P. “A Practical Guide to Successful Outsourcing” (1998) Empowerment in Organizations, Bradford. 6(3) pag. 94.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry. Cooperative manufacturing arrangements for licensed biologics. Rockville, MD; 2008 Nov. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/General/ucm069883.htm.

- Dibon, M. “Exploring Outsourcing – Challenges and Opportunities” (2009) Global Cosmetic Industry page S4.

- Kirk, A. “Benefits of Effective Communication with a Contract Analytical Laboratory – How to handle out-of-specification results in contract analytical work” (2009) Supplement to: BioPharm International pag. 26-32.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Guideline for Drug Master Files (DMF). Silver Spring, MD; 1989 Sept. Available from: www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/FormsSubmissionRequirements/DrugMasterFilesDMFs/ucm073164.htm.http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm122886.htm.

- US Food and Drug Administration. SOPP 8403: Issuance and Reissuance of Licenses for Biological Products. Silver Spring, MD; 1999 April. Available from: www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ProceduresSOPPs/ucm073468.htm. http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ProceduresSOPPs/ucm073468.htm.

- Woo, J., Wolfgang, S. & Batista, H. “The Effect of Globalization of Drug Manufacturing, Production, and Sourcing and Challenges for American Drug Safety” (2008) Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 83(3) pag.494-497.

- Linna, A., Korhonen, M., Mannermaa, J., Airaksinen, M. & Juppo, A. “Developing a tool for the preparation of GMP audit of pharmaceutical contract manufacturer” (2008) European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 69 pag. 786-792.

- Garcia, M. “FDA Recommendations to Industry Regarding Outsourcing – How to ensure compliance in the outsourcing environment” (2009) Supplement to: BioPharm International pag. 6-9.

Marlene Garcia Swider has served in the FDA for more than 22 years in different capacities including Reviewer, Budget and Planning Analyst, Investigator and Project Manager. Most recently she serves as the Quality System Manager for Los Angeles District Office, FDA. She is currently pursuing a doctorate degree in Organizational Management. The information presented in this article was part of her FDA presentation tothe American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists (AAPS).

This article was printed in the May/June 2011 issue of Pharmaceutical Outsourcing, Volume 12, Issue 3. Copyright rests with the publisher. For more information about Pharmaceutical Outsourcing and to read similar articles, visit www.pharmoutsourcing.com and subscribe for free.