With the publication of the European Good Distribution Practices (GDP) guideline, to better protect the pharmaceutical supply chain - referencing EMA Guidelines in 2013 – all actors in the pharmaceutical supply chain are obliged to perform a full review of all associated Quality Systems to determine current compliance status, as well as address gaps, thus ensuring compliance in accordance with the guideline.

GDP compliance ensures that the quality of medicinal products is maintained throughout all stages of the supply chain, from the site of the manufacturer to the pharmacy or person authorized or entitled to supply medicinal products directly to the end user, the patient. Its purpose:

- To safeguard product quality and integrity to avoid patient safety impact;

- As well as prevent unnecessary product loss or scrap to ensure availability of medicinal products to patients;

Within the referenced EU GDP guideline, supply chain security requirements are described with a significant level of importance. However, to date, pharmaceutical industry standards for preventive supply chain in-transit security measures have yet to be universally defined and accepted.

Introduction

Cargo theft is a significant concern in the pharmaceutical supply chain as unnecessary product loss may result in (restricted) unavailability of medicinal products to patients. To safeguard product quality, efficacy, safety and security of all pharmaceutical goods to the patient, Supply Chain Security Risk Assessments towards in-transit activities are essential. In this article, we outline a comprehensive ‘Shipping Lane Security Risk Assessment Model’ and important ‘Shipping Lane Security Risk Assessment Criteria’. This is followed by listing preventive measures in order to increase the level of security. It supports global harmonization for in-transit supply chain security requirements, as well as to offer risk assessment guidance with focus on road transportation security.

Regulations

Transporting pharmaceutical products and production materials, throughout the manufacturing, packaging, warehousing, and distribution processes is recognized as an integral part of the Supply Chain. This includes the movement of materials at all the various stages of a product’s life cycle: acquisition of ingredients, manufacturing the product, packaging the product, storage and distribution of the product, as well as recovery of unused or recalled product for destruction, and would encompass all the transit and storage occurring in-between these events.

The transportation processes must be in compliance with all applicable regulatory requirements and be performed in a manner that ensures the safety, identity, strength, purity, and quality of the products are maintained during the transit activities. Additionally, those activities must include appropriate security measures to minimize the potential for theft, diversion, loss, tampering, etc.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers have a responsibility to ensure product quality safety and efficacy in accordance with GMP/GDP regulations. For larger pharmaceutical manufacturers, their Quality Management System (QMS) have a global reach to ensure compliance with Good Distribution Practices, based on local market needs. The EU GDP guideline1 can be used as a solid basis for this QMS. However, with increasing focus on supply chain security requirements during transportation, dovetailed with increasingly complex supply chains, it is important to assess and document the transportation risk2 within the supply chain.

Cargo Theft

The trading and the use of falsified (counterfeited) medicinal products, which can be potentially toxic or simply ineffective, is one of the major threats to global health and safety, involving both developing countries as well as industrialized ones.

Cargo theft is one of the critical risks pharmaceutical manufactures and their associated supply chains must face, since it could lead to unlawful product diversion, adulteration and counterfeiting, which could have a direct impact on patient safety as well as damage the brand and company reputation. These types of incidents can also have a significant

financial impact - from product loss resulting in potential revenue loss. Several studies have recently been conducted on pharmaceutical product losses due to theft, in an attempt to identify the total cost of such a loss. One such study published by the University of Texas’ College of Pharmacy3 surveyed a broad group of professionals in the pharmaceutical space and placed this cost at between three and five times the product value when indirect and potential recall costs are factored in.

Rx-360’s Supply Chain Security Working Group has also looked at the total cost of loss seeking to justify a positive return on investment to offset program costs. As part of that work they have created a worksheet that can be used as a tool to help determine this cost.4

Recent statistical analysis has shown that, due to significant improvements in facility security, the vast majority of thefts of pharmaceutical products occur when shipments are in-transit. A number of captured cargo cargo thieves have been in the past, apprehended either during or after a pharmaceutical in-transit theft. Those individuals have indicated the profits from selling stolen pharmaceutical goods is highly attractive to sophisticated criminals.

According to Sensitech Inc. and its risk-management services group, SensiGuard,5 approximately 75% of all cargo thefts in EMEA are related to freight transported by road. The market value of all types of goods stolen from road transport in the European Union (EU) was approximately €11.6 billion in 2013. Of that 11.6 billion at least 1% was believed to have involved pharmaceutical products. That being said, one must also keep in mind that the reporting of pharmaceutical thefts, by those victimized, is notoriously underreported.6

According to Transported Asset Protection Association (TAPA), a nonprofit organization, and their recently published TAPA EMEA Incident Information Service (IIS) data7 for the first six months of 2017 the statistics generated reinforce the need for more secure parking for vehicles transporting high risk/high value commodities, such as pharmaceuticals. Of the 950 cargo crimes reported for the period from 1 January - 30 June 2017, 694 or 73% of theft incidents occurred in unsecured parking places, at a rate of 4.5 a day. Latest intelligence7 shows 75% of all newly-recorded incidents took place in such parking locations.

Over 93% of cargo thefts involved trucks in May-June 2017

A total of 160 cargo crimes in May and 188 in June were reported to TAPA EMEA. The number of these crimes reinforces the need to improve security for trucks and drivers. The top five incidents are all vehiclerelated: (1) Theft from Vehicle, 77% (2) Theft of Vehicle, 5%, (3) Hijacking, 4%, (4) Theft from Trailer, 4% and (5) Theft of Trailer, 3%. In comparison, there were only three cases reported in May involving Theft from Facility.

Particularly alarming is that these cargo crimes seem to be on the rise. The SensiGuard Supply Chain Intelligence Center (SCIC) recorded a total of 2,240 incidents in 20168 which entailed an increase of 270 additional incidents in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa (EMEA) region as compared to 2015. Of those thefts, approximately 75% took place in areas with unsecured truck parking. This particular statistic indicates that a critical aspect of securing one’s supply chain should include performing a thorough risk assessment of all shipment lanes – particularly ones long enough require stops in-between destinations.

Also of note, in the analysis of SensiGuard data, was that several pharmaceutical cargo thefts involved “hijacking” activity. There were approximately 99 hijacking incidents in 2016, according to the SensiGuard SCIC, most of which occurred while in-transit. One location where these types incidents are also regularly being seem to be rising is in the country of South Africa.

In Brazil, there were about 22,550 cargo thefts in 2016 (according to Rio de Janeiro State Industries Federation), an increase of 22% as compared to 2015. The States of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro were responsible for 87% of cargo thefts of the country.

Underreporting continues to be an acute problem in Mexico, however, reported thefts increased 62%. The states of Guanajuato, Queretaro, Estado de Mexico, Puebla and Veracruz represented 60% of all recorded thefts.

For the year 2016, the SensiGuard SCIC recorded 857 cargo thefts throughout the United States and Canada. Although the total number of incidents rose only marginally, the threat of cargo theft continues to grow in the United States due to increased organization and innovation on the part of cargo thieves as they broaden their geographical areas of operation and improve their methods to avoid detection and capture.

Underreporting

Elsewhere in Europe, the true picture of thefts from supply chains is far less clear as TAPA continues to seek reliable and regular sources of intelligence. The number of recorded crimes in the other countries, therefore, should not be seen to imply they are any more, or less, secure for high value, targeted goods in-transit.

The high risk areas in Europe more or less are assumed to be equal to the heatmap (see Figure 1) showing Europe’s most desirable logistics locations. This is aligned with the basic principle of supply chain security: cargo at rest = cargo at risk.

Figure 1. SensiGuard SCIC Heatmap Europe

Figure 1. SensiGuard SCIC Heatmap EuropeOne must also bear in mind that the “classification” of cargo crime varies from one law enforcement jurisdiction/country to another – making the overall accuracy of statistics difficult to judge.

Risk Assessment

A risk-based approach is essential for creating a practical supply chain security standard for all supply chain partners. The EU GDP guideline recommends all actors in the supply chain adapt such a risk based approach when referring to the ICH Q9 Quality Risk Management standard.2

The “Guidance for Industry Q9 Quality Risk Management” document issued by the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH)2, also referenced in the EU GDP guideline, outlines principles and tools for quality risk management as it pertains to pharmaceutical quality. The Q9 document categorizes a risk assessment into three parts: Risk Identification, Risk Analysis, and Risk Evaluation. This, along with much of the Q9 document’s tools and principles, can be applied to the supply chain security risk assessment for shipping lanes as well.

The Shipping Lane Security Risk Assessment Model shows the different elements of the Risk Management Program and how they interact. The most logical starting point is obtaining a better understanding of each individual supply chain and then by creating a visual documentation of that supply chain with a map.9 Proper change control of such maps is important in keeping them accurate.

Supply chain maps can be created either by focusing on individual products or by shipping lane (market), and should highlight their characteristics. These mapping efforts should not be limited to the regular flow. Maps should also be created that would include reverse logistics. Return flow and destruction of goods are considered just as high of a risk when considering one’s overall supply chain, hence the Shipping Lane Security Risk Assessment Model should also be applied for reverse logistics.

Figure 2. Shipping Lane Security Risk Assessment

Figure 2. Shipping Lane Security Risk AssessmentSupplier management is a key element of the supply chain security risk management program. It should also include any entity involved in subcontracting. Any agreements between a pharmaceutical manufacturer and their logistics service providers needs to automatically apply to the contracted partners of the service provider. The supplier must have a supplier management program in place and this should be audited by the contract giver. On a regular basis the performance of suppliers must be monitored using a form of agreed upon performance indicators.

Rules of the Road

Typically, suppliers provide to their contracted transportation entities documentation of “rules of the road”, or a set of detailed instructions for both the carrier and drivers on how to best behave when transporting high value goods.

A risk-based approach to monitoring transportation security typically involves the supplier’s status of the transportation carrier (approved, audited, certified, etc.); the mode of transport (road, air, ocean, rail or multi-modal); the distribution model (Full Truck Loads, FTL or Less than Truck Loads, LTL); the level of subcontracting and cross-docking; the level of awareness, experience and training of everyone involved; the volume and value of the products transported; the overall transit time; as well as training, and the available intelligence concerning number of the route and its past history of security related incidents.

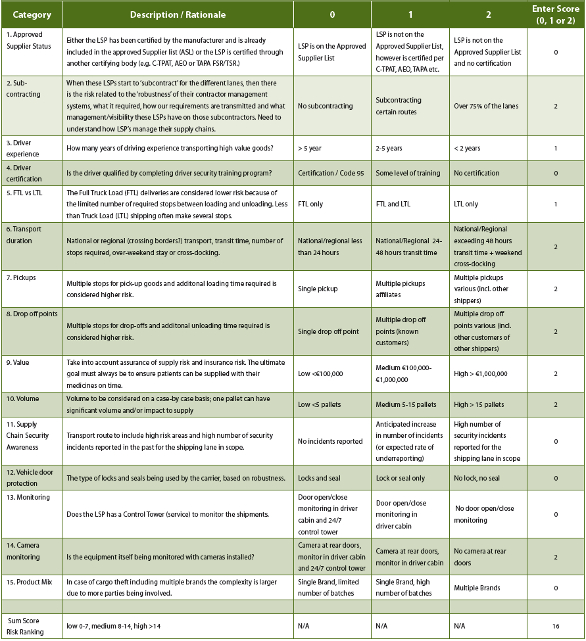

Table 1 shows an example of performing a supply chain risk assessment using a basic risk ranking tool. Various security attributes are assessed and assigned numerical risk values. Risk can be scored in various ways: ‘1, 2, 3’ or ‘0, 1, 2’ or ‘1, 5, 10’. In this case we selected ‘0, 1, 2’ in order to keep it rather straightforward (see Table 1).

Table 1. Shipping Lane Security Risk Assessment Criteria

By totaling the numerical values an overall risk value/score is generated. Based on that overall value/score, action either is - or is not then – required, per the criteria identified. Another option is to add weighing factors to the criteria and have the individual scores multiplied by the weighing factor assigned to the criteria concerned.

Note: these are examples; the number of listed elements is not comprehensive and may depend on the shipping lane and the value of the cargo.

Additional factors to be considered include, but are not limited to: external risks (e.g. country situation, trends in markets, regional political events, cargo crime intelligence, infrastructure) and, type of medicines (e.g. life-saving, narcotic, Rx, OTC, consumer goods, etc..)

Security Preventive Measures

There are a number of publications available relating to in-transit security. Some of them are referenced in this paper and several will be listed in the bibliography at the end of this paper. From those documents, as well as established supply chain security programs, the following precautions should be given consideration as a minimum standard of implementation. Bear in mind, however, the level or intensity of measures to be implemented will vary - sometimes greatly - depending upon: the identified risk level against the product being moved; the areas in which the product will be moved; the planned transit times; as well as local and international regulations.

Carrier Instructions

Carrier instructions, sometimes referred to as contractual Logistic Service Provider (LSP) instructions will have to be made as part of the agreed partnership between the shipper and the transportation entity.

These instructions should include such topics as: confidentiality, hiring of personnel; driver rules; secure handling of freight in-transit; shipment tracking; notifications in case of incidents; required response time etc. Again, these instructions are typically described in legally binding contracts, Quality Technical Agreements (QTA) and/or Service Level Agreements (SLA’s).

Driver Instructions

Shipment delivery drivers play a key role in the supply chain. They, essentially, are the lone custodians (at least physically) of pharmaceutical goods while they are in-transit. When that transit is lengthy, or passes through areas of high risk - due to crime or economic strife - their attention to detail becomes all the more important. Hence, anyone who transports pharmaceutical goods must be made to feel a genuine part of that supply chain process. To do that involves consistent positive reinforcement; personal interaction; and, above all, thorough training in what is required of them.

Being thoroughly versed in what is required; being made aware of the latest security-related intelligence which may affect their route, as well as being taught how to heighten their general sense of awareness, and how to respond in case of incidents, will significantly minimize drivers from exposure to many security incidents.

The set of ‘driver rules’ may vary based on the value and the volume of goods being carried, as well as considering the level of risk-based on the result of a shipping lane security risk assessment. However some basic rules should always apply, such as: being prepared before loading to avoid unnecessary stops shortly after departure, (fully fueled vehicle, drivers with required rest, near time consumption of food); avoiding documented high risk areas; avoiding unsecured areas; as well as minimizing any times when the delivery vehicle would be left unattended.). In the latter case, the utilization of dual drivers is an excellent mitigation strategy to avoid a totally unattended vehicle.

Shippers should consider a formal Driver Departure Interview (DDI) process during the assignment of the shipment to a driver. Drivers should be required to read and sign that they understand the expectations and standards of care required for transport of the particular load they have been assigned.

In addition to obtaining the driver’s written acknowledgement to the required standards of care, a short driver interview/conversation should also be conducted. Any suspicious responses during that interview should trigger additional questions and, if needed, escalation for additional verification. With the sophisticated cargo theft tactics of “falsified pickups” and “identity theft” on the rise, these steps at the interview stage will help to mitigate those risks.

Creating a security awareness and culture starts with driver education, as well as setting clear expectations for each driver. Lastly, ongoing monitoring of driver behavior is critical to the ultimate success of the program.

Driver Training

All transportation service provider employees, in particular drivers, should receive regular security training throughout their employment. That training should be documented, as well as signed off by each participant. Training records should be made available for review by shippers who employ the service providers.

Training topics should include:

- Corporate security responsibilities

- Customer-specific security responsibilities

- Awareness training

- How to detect suspicious activity

- Latest intelligence information of prevalent methods of illicit theft/ diversion tactics

To encourage positive participation in company-based security efforts, it is suggested that transportation service providers employ a reward program; recognizing employees who provide useful intelligence or act in ways that further safeguard pharmaceutical shipments in transit. It is also encouraged that shippers themselves, endeavor to personally visit with and offer encouragement to drivers whenever possible.

Making a driver, feel that they are genuinely a part of the importance of the pharmaceutical supply chain will go a long way in maintaining its integrity. Even simple things like providing rest room facilities, access to vending machines; or an employee a cafeteria, can help with inclusiveness and ensure the driver is prepared to drive a significant distance from the facility.

Equipment and Product Protection

Hard-sided trailers are the preferred conveyance for pharmaceutical products. Soft-sided trailers should be avoided whenever possible.

According to the risk management entity BSi, an increasingly high rate of cargo theft plagued freight shippers in Germany in 2016.10 BSi analysis indicated nearly half of all cargo truck thefts in Germany were pilferage incidents in which thieves slashed into the tarpaulins of trailers to steal cargo. Germany is not alone suffering these types of pilferage loss. BSi has indicated that these.

Thefts frequently occurred when freight shippers parked overnight in unsecured, poorly lit rest stops along major highways.

Also important is sufficient sealing of the cargo.

Sealing of cargo is a shared responsibility between shippers and transportation service providers. Shippers need to make sure the goods leave their premises in a sealed truck, trailer or container. There are various types of seals available, the most popular being either “bolt” or “cable” seals. Some companies go as far as to photograph an attached seal and forward it to the consignee for comparison upon arrival. This would be considered a “best practice”.

Driver’s need to frequently check the integrity of cargo seals throughout the shipment trip. Any breach indications need to be immediately reported to the shipper.

Risk Mitigation – Monitoring Solutions

The use of small, in many cases, real-time monitoring devices may be one way to bolster an in-transit security program. Specialized devices have been on the market for years and utilize many of the advancements made in the general cellular industry to offer better accuracy and better signal strength/coverage. With these advancements additional sensor readings for location, temperature, humidity, light, shock vibration and tampering were introduced. Companies providing these services often have the ability to reach out directly to carriers to inform and actively mitigate potential risk, thereby reducing the shipments overall exposure to pilferage, theft, environmental change, or delay. Data from these services can also be aggregated and reported to increase supply chain visibility to each supply chain partner adherence to agreed-upon standards of care.

Supply Chain Visibility and Supply Chain Maps

Carriers who already utilize global positioning system (GPS) tracking technology in their fleets should be the preferred vendors of choice. Trucks and trailers should be equipped with GPS to ensure real time tracking and tracing of shipments 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year. Services that monitor driver behavior proactively are also extremely beneficial when it comes to reducing theft exposure. This data can also be compiled and used to measure continuous improvement and that standards defined in any QTA are being adhered to.

As previously stated, it is beneficial to have created supply chain maps in advance of any shipment activity.

The maps should include any entity or individual that would come in contact, or “touch,” the product as it moves through the supply chain - to include manufacturers, wholesale distributors, retail distributors and reverse distributors - as well as any transit method (road, air, ocean or rail) that move the materials from point-to-point.

Although all partners in the supply chain are responsible for maintaining the quality and integrity of materials while in their custody, pharmaceutical manufacturers are principally held responsible for quality, safety and security as goods pass throughout the supply chain.

Supplier Qualification and Control

A pharmaceutical supply chain must be well controlled and monitored through the use of approved GDP compliant warehouses and logistic service providers.

A supplier evaluation program should be utilized to evaluate and approve third party warehouses and logistic service providers. To be effective, the evaluation program must require the use of on-site audits to confirm the compliance of the service provider with the stated contractual security obligations as well, if applicable, with GDP and implementation of QTA or SLA.

A standard QTA template, aligned with the GDP guideline, should be established with all logistic service providers. The requirements agreed upon between the contract giver and its contracted service providers automatically apply to the next level contracted partners in case of subcontracting.

Reverse Logistics

In many instances, when it comes to the secure movement and storage of goods in the reverse logistics process, things are less described or documented Being a high risk activity as well, reverse logistics should be treated as any other sensitive pharmaceutical shipment, to include transportation arranged for product for destruction. In reality, rejected product and product awaiting destruction has a greater potential of being falsified, re-used and reintroduced on the market. Strict control of the shipping process, and the actors involved, is therefore essential.

Supply Chain Security Awareness

Supply chain security awareness comes from the sharing of intelligence – not only between shippers and recipients, but also those that support shipping activities – such as transportation security providers. The sharing of intelligence is critical to keeping pharmaceutical products safe from theft and diversion.

The level that supply chain partners, upstream and/or downstream in the supply chain, are aware of the potential security risks depends upon their participation in intelligence sharing mediums - be they in the private sector such as Rx-360, PSI, PCSC, TAPA, Sensitech , BSi, - or government driven, such as AEO and C-TPAT programs.

According to BSi’s 2016 Global Supply Chain Intelligence Review Report10 greater enforcement efforts as well as industry demands for more secure parking and hard-sided trailers signify a growing understanding of the cargo theft environment. TAPA EMEA will soon introduce its new Parking Security Requirements (PSR) to Parking Place Operators (PPO) in Europe.11

If, during the course of a contractual agreement, a threat to a shipper’s product, or the carriers’ equipment/personnel emerges; both parties must agree to notify each other of the increased threat and cooperate to identify protective measures to mitigate the risk.

Further Recommendations for Transit Through High Risk Lanes

- Driver identities should be confirmed prior to the loading of any conveyance. It is preferred that shippers are provided both driver information (to include photos) as well as vehicle information (to include make, model, license number, Vehicle Identification Number (VIN) number) at least 24 hours prior to the actual pick-up of the shipment.

- Security assessments (whether through available intelligence or through personal visits) of potential locations along the shipment route, where stops might take place, should be conducted.

- Stops that include good visibility, adequate exterior lighting, Closed-Circuit Television (CCTV) surveillance coverage, and perpetual law enforcement patrols, are to be considered preferred rest/refueling locations.

- Extended stops in high-risk areas, particularly during evening hours, should be avoided if at all possible.

- In high risk shipment situations, the preferred employment would be of a “two-person” driver “team” to reduce the risk of a delivery conveyance being left unattended.

- Visible driver “habits” should be considered when planning shipment trips. Repetitive behavior (such as always stopping at the same truck stop, always taking exactly the same route to destination, etc...) should be avoided – as it makes the shipment trip more predictable for those with illicit intentions.

- The latest technical solutions for conveyance security now include the use of CCTV camera systems inside trailers to monitor door openings. This type of camera system should be in place within a trailer/van to monitor opening/closing of doors.

- Finally, consideration should be given to hiring a contracted “escort” service to both guide and monitor high-risk shipments in transit.

Conclusion

Risks associated with each step in the supply chain must be evaluated and mitigated, from raw material sourcing to ultimate reverse distribution. Organizations should have a full appreciation of every step of their respective supply chains – in particular any in-transit facet of that supply chain. This should be documented in risk assessments performed on shipping lanes, focusing on the supply chain security aspects.

Organizations need to be cognizant of any potential threats and be ready to challenge and defend against those threats successfully. The ultimate recipients of their products and diligent efforts, patients all over the world, are dependent on those critical achievements.

Through active collaboration with professional colleagues, industry organizations; like PDA, PCSC, TAPA, Rx-360, EFPIA; and programs such as Customs Trade Partnership against Terrorism (C-TPAT) and Authorized Economic Operator (AEO), can be benchmarked for best practices as well as to improve evaluations of in-transit risks to one's respective supply chains.

Governments, industry groups, trade associations and Health Authorities can highly contribute in raising awareness on the potential risks in pharmaceutical supply chains by initiating campaigns and communicate to the public.

Disclaimer

This paper was put together by a voluntary pharmaceutical industry working group.

The content and the view expressed in this document are the result of a consensus achieved by the authors and are not necessarily views of the organizations they present or represented.

The mention of a product or service provider does not mean it is the sole product or service that is available for use.

References

- EMA Guidelines of 5 November 2013 on Good Distribution Practice of Medicinal Products for Human Use (2013/C 343/01) (https://ec.europa.eu/health/human-use/good_ distribution_practice_en).

- International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Guidance for Industry Q9 Quality Risk Management” (ICH Q9) (http://www.ich.org).

- Pharmaceutical Cargo Theft: Uncovering the True Costs, by Dr. Marv Shepard Ph.D., Professor and Director of the Center for Pharmaeconomic Studies, College of Pharmacy, University of Texas at Austin, Texas, 2014 (http://www.sensitech.com/en/resources/white-papers).

- Rx-360 White Paper: Cargo Theft in the Pharmaceutical Industry, What does it really cost? (http://rx-360.org)

- Freightwatch ‘Pharmaceutical Cargo Theft in Europe, A Realistic View Of The Current Trends, Challenges, and Financial Impacts’, Helmut Brüls & Daniel Wyer (http://www. sensitech.com/en/resources/white-papers).

- ‘Putting a Price Tag on Underreported Cargo Theft in Europe,’ Helmut Brüls & Daniel Wyer (FreightWatch International), 2015 (http://www.sensitech.com/en/resources/white-papers).

- TAPA EMEA Incident Information Service (IIS), Small fall in incidents in June but losses still exceed €7.9M, (https://www.tapaemea.org).

- SensiGuard Supply Chain Intelligence Center (SCIC) Cargo Theft Report 2016 (http:// intelligence.sensitech.com/).

- Rx-360 Upstream Supply Chain Security White Paper, 14 April 2014 (http://rx-360.org).

- BSi 2016 Global Supply Chain Intelligence Review (https://www.bsi-intelligencecenter.com).

- TAPA Standards, Parking Security Requirements, PSR 2017 (https://www.tapaemea.org).

Bibliography

- Rx-360 Supply Chain Security White Paper “A Comprehensive Supply Chain Security Management System” (http://rx-360.org).

- Bishara, R. H., and Griggs, S.: Adopting the TAPA cargo security standard in the pharmaceutical industry. Pharmaceutical Commerce, Sep.-Oct. 2014, Volume 9, Issue 5, pp. 34 – 35.

- TAPA Standards, Trucking Security Requirements, TSR 2017 (https://www.tapaemea.org).

- PDA TR 52 - Guidance for Good Distribution Practices (GDPs) for the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain, August 2011 (https://www.pda.org/publications/pda-publications/pdatechnical- reports).

- PDA TR 58 - Risk Management for Temperature-Controlled Distribution, September 2012 (https://www.pda.org/publications/pda-publications/pda-technical-reports).

- CARTS’ Cargo and Road Transport Security Guide, April 18, 2017, (https://issuu.com/ maplemarketing8/docs/cart_security_guide_12mb).

- AEO, European Commission Directorate-General Taxation and Customs Union (TAXUD). Authorised Economic Operators - Guidelines 2016 (http://ec.europa.eu/taxation_ customs/general-information-customs/customs-security/authorised-economicoperator- aeo_en).

- United States Pharmacopoeia (USP) <1079>, “Good Storage and Distribution Practices for Drug Products”.

- United States Pharmacopoeia (USP) <1197>, “Good Distribution Practices for Bulk Pharmaceutical Excipients”.

- World Health Organization (WHO) Technical Report Series, No. 957, 2010, Annex 5, WHO good distribution practices for pharmaceutical products.

Glossary

(Arranged alphabetically)

AEO: Authorized Economic Operator.

ASL: Approved Supplier List.

BSI: British Standards Institution.

CCTV: Closed-Circuit Television.

C-TPAT: Customs Trade Partnership against Terrorism.

DDI: Departure Interview (DDI).

EMA: European Medicines Agency.

EMEA: Europe, Middle East and Africa.

EU: European Union.

FSR: Facility Security Requirements.

FTL: Full Truck Loads.

GDP: Good Distribution Practices.

GMP: Good Manufacturing Practices.

GPS: Global Positioning System.

ICH: The International Conference on Harmonization.

IIS: Incident Information Service.

LSP: Logistic Service Provider.

LTL: Less than Truck Loads.

MHRA: Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (UK).

PCSC: Pharmaceutical Cargo Security Coalition.

PDA: Parenteral Drug Association.

PPO: Parking Place Operators.

PSR: Parking Security Requirements.

QMS: Quality Management System.

QTA: Quality Technical Agreements.

Rx-360: An International Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Consortium (non-profit).

SCIC: Supply Chain Intelligence Center.

SLA: Service Level Agreements.

TAPA: Transported Asset Protection Association.

TSR: Transport Security Requirements.

VIN: Vehicle Identification Number.