As another wave of the COVID-19 pandemic surges across the globe, patients are flooding into hospitals, economies are returning to lockdown and supply chains again face restrictions. This second wave has renewed fears of drug and medical device shortages, and given new life to conversations in the United States about national security and overreliance on manufacturing in other countries. While our current environment amid the pandemic may spur politicians and companies to examine reshoring supply chains, the reality is that our supply chains and manufacturing capabilities have been intentionally offshored over the last few decades for one reason: cost.

As much as we may want to believe in the altruistic motives of reshoring (namely domestic job creation and economic self-sufficiency), it will take government regulation and monetary incentives to drive substantive change. Due to complexity and cost structures, there is limited reason to expect widespread supply chain reorganization in the immediate future. In the long term, however, there is a valid argument for reexamining the domestic approach to manufacturing and identifying ways to increase supply chain resiliency and manage exogenous exposure.

There is limited political risk in emphasizing reshoring as a means to create jobs and decrease reliance on foreign entities, while ignoring the reasons behind the status quo. Manufacturing in America can be orders of magnitude more expensive and complicated due to our strong currency, tax structures, cost of labor and robust regulatory structures, and tackling such topics requires significant political effort.

What likely makes more sense are policies that incentivize companies to increase targeted portions of their supply chain domestically in the near term, while evaluating long-term structural changes.

Nearshoring, and more generally outsourcing, have favorable outcomes compared to a pure reshoring strategy, mainly that supply and production risk can be diversified, partners with specialized skills and knowledge can be selected to complement existing capabilities, and companies can take advantage of more favorable tax and regulatory structures until further clarity is achieved in the U.S. Many companies will find that a combination of nearshoring, outsourcing, and domestic support for R&D and manufacturing is a more balanced and sustainable solution.

Reality of Perceived Risks

The pandemic has intensified supply chain pressures throughout the broader economy, but the life sciences ecosystem has received a particularly high level of scrutiny because this recession was brought on by a crisis to public health and safety. While the life science industry has been applauded for its efforts in combating the pandemic, it has also come under intense pressure to ensure a consistent supply of therapies, medical equipment and supplies. Overall public perception and understanding of the industry has benefited in 2020, but life sciences companies have also been an easy target for politicians and the media to focus on how much some elements of the life sciences supply chain have been outsourced and where vulnerabilities exist.

While there were major shortages of ventilators and personal protective equipment, those were driven by an unprecedented demand shock and limited capacity of national stockpiles. The U.S. manufacturing sector, supported by processes that have become more nimble and automated, was able to quickly pivot to fill these needs.

The pandemic has been a lesson in how to do more with less in the face of unprecedented adversity. That is one reason why, in the life sciences industry, we have seen a surge in investment in technology and outsourcing to parties with specialized skills and knowledge.

Even the biotech and pharmaceutical industries – which have far outpaced global market performance – pale in comparison to the life science outsourcing and technology sector.

Still, there was concern about drug shortages as shipping routes were closed and countries froze the sale of certain products to secure their own domestic stockpiles. Fortunately, widespread drug shortages have not materialized. In reality, drug shortages are rarely the result of a single shock such as recession or pandemic, but have been an ongoing issue for the industry and regulators to address, according to information from the Food and Drug Administration.

Drug shortage data tracked by the FDA through October 2020 indicates that of roughly 400 unique drugs facing a shortage, only 30% are in a production shortage and the other 70% are in a shortage because they have been discontinued.1 Of those active drugs in a shortage, only 30% were newly added to the FDA’s shortages list in 2020, and the rest had been listed two years ago on average.2 The three major causes of drug shortages, according to the FDA’s 2019 report on drug shortages, are: the lack of incentives to produce less profitable drugs, a lack of market recognition and reward for mature quality management systems; and logistical and regulatory challenges that make it difficult to recover from a disruption.3 In other words, a lack of generics and biosimilars, a system that prioritizes efficiency over quality, cumbersome regulation, and a lack of excess capacity. Twenty-seven percent of all drug shortages are due to material shortages and 64% are due to manufacturing quality and delays, according to FDA figures.4 These underlying issues would not be addressed through reshoring alone.

The concerns of material shortages and an inability to meter production capacity are inexorably tied to the more macro fear that the U.S. has driven its manufacturing capacity out of the country and has become overly reliant on China.

Branded Versus Generic

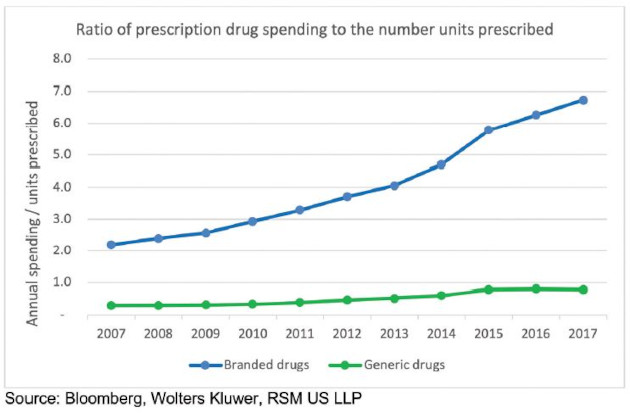

When pundits or politicians reference drugs and drug pricing, they often omit the crucial distinction between branded drugs and generics. The disparity in the quantity of branded versus generic drugs sold in the United States, and more importantly the differences in pricing have shaped today’s global supply chains and created significantly more international exposure for generics.

Approximately 80% of all U.S. prescription drug spending in 2019 was on branded drugs, but those drugs only make up 10% of total prescriptions dispensed, according to data from health care analytics company IQVIA.5 Additionally, because those branded and innovative drugs generate the majority of U.S. drug companies’ revenues, production is located domestically in order to be close to the customer and to protect the intellectual property. According to a 2015 study from Bloomberg, “75% of U.S. spending on drugs is for products that are manufactured domestically,” and the top five international sources (by value) were Ireland, Germany, the U.K., Switzerland and India.6 Other than India, these are not low cost markets, but they are highly skilled and have stable economies and trade ties with the United States, making them reliable partners in a diversified life science ecosystem.

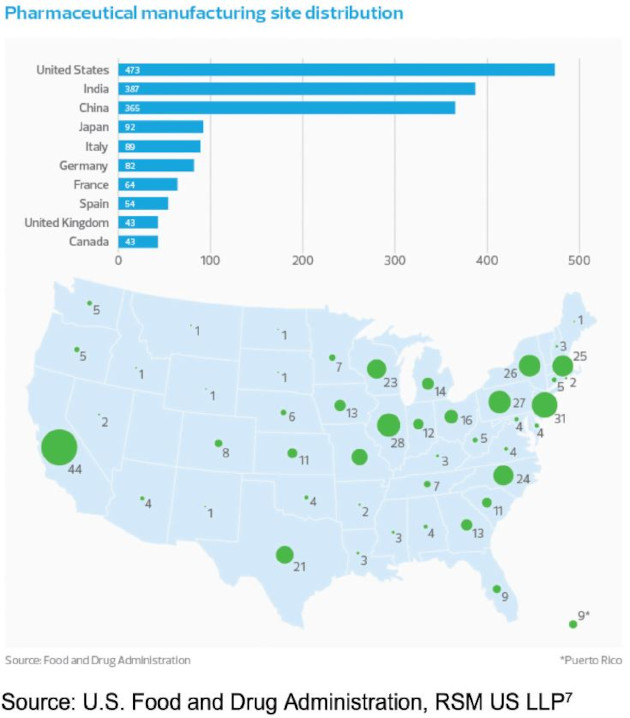

Legislators and industry watchdogs have been critical of the lack of transparency over the distribution of pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities and what portions of the finished product they are responsible for. With the limited supply chain data collected by the FDA, we have used manufacturing sites as the best proxy for the amount of manufacturing taking place in the U.S. and other countries.

Subscribe to our e-Newsletters

Stay up to date with the latest news, articles, and events. Plus, get special offers

from Pharmaceutical Outsourcing – all delivered right to your inbox! Sign up now!

The opacity of information about drug manufacturing operations also brings up another point: As opposed to assuming that companies need to reshore operations, regulators need a clear view of where risk and exposure are concentrated in order to make decisions to support more secure supply chains.

Generic drug production in China is often cited as our largest area of supply chain exposure and the primary motivation to reshore life science manufacturing to the United States. While the majority of drugs prescribed in the United States finish production domestically, the past two decades have seen an almost universal outsourcing of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturing to China and India, which have a lower cost of production and less restrictive labor and environmental regulations. Because 90% of U.S. prescriptions are for generics,8 which have significantly lower margins than their branded counterparts, the economic focus is on decreasing cost and maximizing efficiency, not on ensuring resiliency. As a result of these pressures, approximately 80% of all API manufacturers are outside of the United States, according to the most recent FDA Regulated Products report.9 The nation is currently able to cover only about a quarter of global production capacity for APIs, according to Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.10

In Teva Pharmaceuticals’ Q2 earnings call, President Kåre Schultz said, “It's also true that there [have] been discussions about getting API manufacturing … back into the U.S. It's a fact that it has basically all left the U.S. within the last 30 years, so there is nothing left, which means that getting it back for real would take probably 10, 20 years and would have to depend on major structural changes in pricing and all these kind of elements, as you can imagine.”11

The pressure to manage margins while facing greater competition of generics and biosimilars is highlighted by the relationship of spending to the number of units prescribed. Reshoring generic and API manufacturing would take a major overhaul in EPA and FDA regulations, financial incentives for domestic production or disincentives for offshoring, and an understanding from the public that it would take years to ramp up capacity and likely cause drug prices to rise. These may be acceptable tradeoffs in the long run, but it is a much more complex conversation than what has currently been presented.

A Question of Identity

At the heart of this conversation about supply chains is a much more existential question: What is it that the United States wants to be known for? As the United States has shifted over the years from being a manufacturing powerhouse with an abundance of brick-and-mortar facilities to focusing more on innovation through digital advancements and intellectual property, any approach to readjusting supply chains must also shift. In a global economy where individual companies and countries can decide to focus on invention, design and intellectual property, or manufacturing and logistics, or any combination of these, the real question is not how do we as a country consolidate and control this whole process, but how do we connect the pieces so that operations can be smarter and deliver higher-quality products at competitive prices? Part of the answer is that companies should make measured, strategic outsourcing decisions and continued investment in technology and infrastructure.

Companies should evaluate which changes will add the most value, especially in the context of diversifying supply chains away from China and ensuring international supply chains are not overly concentrated in any one country or region, including the United States. A domestic crisis can just as easily lead to supply chain disruptions, as evidenced by the paper products shortage during the early months of the pandemic. Approximately “90% of all toilet paper purchased in the United States is made in America,” according to the nonprofit group Alliance for American Manufacturing,12 but that didn’t prevent widespread shortages of the product in March and April. It still comes down to companies operating as lean as possible to control costs and meet demand just in time. Greg Guest, a spokesperson for Georgia-Pacific - which makes toilet paper, paper towels and more - said in a March article on the Alliance for American Manufacturing’s website: “We are basically a North American manufacturing company, so it is not any kind of issue like a supply chain disruption from Asia. We primarily manufacture all of our products in the U.S.”13

Rather than making wholesale changes to life science supply chains, which would likely increase costs, raise taxes, and focus efforts away from innovation, it is likely more beneficial for companies to leverage technology and rethink the number, proximity, and specific skills of their partners. These more nuanced, strategic decisions can allow companies to remain flexible, pivot more quickly, and maintain resilience.

References

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Shortages Database. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/drugshortages/default.cfm. Accessed October 28, 2020.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Shortages Database. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/drugshortages/default.cfm. Accessed October 28, 2020.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Report on Drug Shortages for Calendar Year 2019. April 23, 2020:12-13. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/139613/download. Accessed November 4, 2020.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Drug Shortages Infographic. Reasons for Drug Shortages. Accessed November 4, 2020 https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugshortages/drug-shortages-infographic

- IQVIA institute For Human Data Science. Medicine Spending and Affordability in the United States. August 2020. Available at: https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/medicine-spending-andaffordability-in-the-us. Accessed November 5, 2020.

- Ari Altstedter. Bloomberg QuickTake: Where the U.S. Actually Gets Its Drug Supply: QuickTake Q&A. January 17, 2017. Accessed November 4, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-01-17/where-the-us-actually-gets-its-drug-supply-quicktake-q-a

- Adam Lohr and Steve Kemler. Life sciences industry outlook, from RSM’s The Real Economy: Industry Outlook. 2020; Volume 5; 51. Available at: https://rsmus.com/what-we-do/industries/life-sciences/industryoutlook-life-sciences.html. Accessed November 5, 2020.

- IQVIA institute For Human Data Science. Medicine Spending and Affordability in the United States. August 2020. Available at: https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/medicine-spending-andaffordability-in-the-us. Accessed November 5, 2020.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Fact Sheet: FDA at a Glance: Regulated Products Report. October 2019. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/131874/download. Accessed November 4, 2020.

- Janet Woodcock, M.D., Director – Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Testimony before House Committee on Energy and Commerce, Subcommittee on Health; October 30, 2019. Accessed November 4, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/congressionaltestimony/safeguarding-pharmaceutical-supply-chainsglobal-economy-10302019.

- Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. Q2 2020 earnings call transcript. Available at: https://s24.q4cdn.com/720828402/files/doc_financials/2020/q2/TEVA-IL-20200805-2406680-C.pdf. Accessed November 5, 2020.

- Alliance for American Manufacturing article, America’s toilet paper makers are working hard to restock store shelves. Available at: https://www.americanmanufacturing.org/blog/americas-toilet-papermakers-are-working-hard-to-restock-store-shelves/. Accessed October 30, 2020.

- Alliance for American Manufacturing article, America’s toilet paper makers are working hard to restock store shelves. Available at: https://www.americanmanufacturing.org/blog/americas-toilet-papermakers-are-working-hard-to-restock-store-shelves/. Accessed October 30, 2020.

Author Biography

Adam Lohr is an audit partner and life science senior analyst. In addition to providing assurance services to his clients, he also sits on RSM’s national life science team and leads the San Diego office life science practice. His senior analyst responsibilities include advising the firm’s life science care clients and client servers as they work to navigate the rapidly changing industry environment. Adam regularly writes, presents and advises on capital markets, digital transformation, policy and other isues transforming life sciences.